The spine needs to have stability in order to move.

If the core isn’t strong enough to do the job, your brain calls on other muscles. Those chronically tight hip flexors? Yep, they attach to the spine, and if they’re trying to hold your spine together to make up for abdominal weakness, they’ll get tight as a drum for as long as they need to provide that stability.

That’s the great thing about the body. No matter what happens, it always finds a way. Every client who limps, hitches, sticks their butt out, or thrusts their head forward is compensating for something else. The solution isn’t ideal, but the body prefers it the alternative.

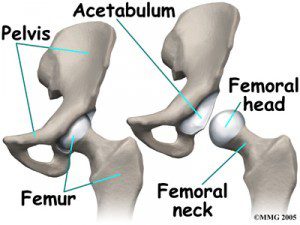

Now if we look at the hip specifically, we see no reason whatsoever that it should be restricted and less than mobile, at least from a structural perspective. It’s a very open ball and socket joint and can go through a huge range of motion before it gets to an actual end-range due to bony contact or capsular ending.

The ease of motion is aided further by synovial fluid to reduce friction, thick cartilaginous lining, a strong but flexible labrum, and positioning on the side of the pelvis to allow the greatest range of motion through multiple planes of movement compared to if it were simply in a hinge formation like the knee or elbow.

It’s my humble opinion that everyone should be able to do the splits, or at least get really close to hitting the floor. This should not be exclusively the domain of gymnasts, dancers, or freaks of nature who can be all bendy and stuff and make people sick to their stomachs by watching their contortions. As mentioned earlier, the hip joint has a lot of motion available to it, which means it should be easy enough to get into the splits if the soft tissue isn’t holding tension for some other area of the body not having the stability necessary.

The splits is something that I’ve just recently been able to work towards, and it’s only really been something I’ve noticed since I’ve been able to get over 425 in the deadlift. In order to get there, I’ve had to work a lot on lumbar stability and core activation due to an old SI joint injury.

To highlight the kind of limitation I have, look at the difference between my left leg going forward and my right (it was a right SI joint issue), and then compare the video of the splits above with my performance in a seated toe touch that would best be described as, well, cryptkeeper-like.

Now compare the seated version to a standing version, where the active and passive restraints are switched around:

The disparity between different movements all affecting the same joint is one reason why SI joint issues are so tough to nail down and train effectively, but essentially it can boil down to a simple concept: the joint is unstable, so other areas become tense to try to provide the stability needed to move without pain.

So what do you do if you have tight hips? Well, there’s a couple different types of “tight.”

If I were to move your hip around through a simple passive assessment, you should have no restrictions in any direction because there isn’t any muscle tension holding it back, or at least there shouldn’t be any muscle tension.

If you’re tight in only one or two specific directions, that shows that there may not be any specific structural limitation, but most likely a movement or stability restriction. If you have no restrictions to movement, yet always complain of being “tight or stiff,” you’re probably hypermobile and the muscles are working overtime to try to provide extra stability.

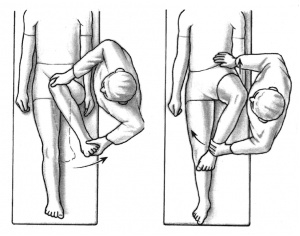

Let’s say you can perform a standard Thomas test, where you bring your knee to your chest and let the opposing leg hang down, checking to see what kind of available hip motion you have through the saggital plane.

If you can hold the knee to your chest and have the opposite knee touching the table, you’re good, dude.

Now comes the voodoo. Let’s say you can get your knee to your chest and have the opposite knee dangle loosely on the table, easy peasy, no problem-o. But maybe you have a serious restriction through rotation, specifically internal and external rotation? That would be a sign that something isn’t quite right.

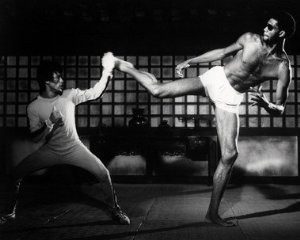

The ability to rotate the hips is pretty important, letting you do everything from walking to hitting a good squat, to engaging in extra-curricular activities with people you find attractive. Here’s a great example to fantastic external rotation exhibited by Bruce Lee, and weak external rotation as exhibited by Kareem Abdul Jabbar from the movie “Game of Death.”

The ability to rotate the hips is pretty important, letting you do everything from walking to hitting a good squat, to engaging in extra-curricular activities with people you find attractive. Here’s a great example to fantastic external rotation exhibited by Bruce Lee, and weak external rotation as exhibited by Kareem Abdul Jabbar from the movie “Game of Death.”

As going through a Thomas test is so decisive regarding the total mobility of the hip, there should be no reason why the hip should be limited through rotation, which means something is holding it back not related to the structure of the joint.

For those of you who have spent years stretching “tight” hips and had no real improvements, you’re chasing the wrong rabbit down the wrong hole.

If the muscle is actually tight, it should be able to become less tight by stretching, and those gains should be permanent if they are appropriate to the restriction. The muscles are hanging on to give stability to some other part of the body, probably the lumbar spine.

The muscles of the hip that resist internal rotation are primarily found on the lateral aspect of the hip.

These muscles play a key role in providing lateral stability to the spine along with the obliques, psoas, serratus anterior and latissimus dorsi. This is where the side plank comes in. It can help to stimulate these muscles and force them to work together to help stabilize the spine in a position that doesn’t allow compensation, and therefore can re-set the hip and core to allow the hip to move properly. Throw a leg raise in there and you have some ultra-mega-power lateral stability.

The muscles that resist external rotation are primarily found on the medial and front of the hip, and have a high correlation to anterior core instability. This is where the front plank comes in. When done properly, the hip flexors are held in a stretched position while the rectus abdominis is working in conjunction with the obliques and glutes to provide the best pelvic and spinal stability possible.

A good front plank should make your glutes incredibly tired from forcibly making them contract so that your hip flexors stretch and the abs bite down harder.

As an example of these concepts during the workshop in Tusla, I had one volunteer who had a history of anterior abdominal issues (pregnancies that resulted in a still-present diastasis recti, or a separation of the two sides of the six-pack muscle) and tested her hips.

She had full flexion through the Thomas test, had decent internal rotation, but had barely any external rotation. Normal means that holding the hip flexed to 90 degrees, the leg should be able to be brought across the body to be in line with the opposite hip, or 90 degrees external rotation. These are just rough numbers, but they tend to hold up well with a wide selection of people.

So she had really poor external rotation. Instead of giving her the littany of hip stretches that wouldn’t do anything to fix the problem, I had her do a front plank, getting really specific to make sure she was in a neutral spine, getting a hard glute contraction, and making sure she was taking full deep breaths. She held this for about 15 seconds, or 3 deep breaths, and then I re-tested her hips.

“Oh my GAAAAAAAAAHHD!!!!” I believe were the words out of her mouth when she now had full external rotation range of motion. Again, we didn’t do any “stretching,” but she improved her range of motion dramatically, so much so that in 15 seconds she saw a greater increase in hip mobility than she’d seen in 10 plus years by working on different stretches and common kinesiological approaches to tightness versus stiffness.

This wasn’t a one-time thing. I’ve had dozens of clients get similar results, and done the same thing at different seminars I’ve taught. Here’s an example from a recent one:

Again, the hip SHOULD be mobile, and any limitation to the mobility typically comes down to a lack of stabilization through the core, and also from the foot hitting the ground in a wonky manner.

By fixing the core specific to the limitation, the hip should loosen up immediately and make you all happy and gumby-like, as long as there isn’t a structural issue at play.

I know this goes against a lot of what is commonly taught out there relating to how tight muscles should be stretched, but that model hasn’t been working, otherwise we would be able to see complete resolution of issues by a few simple stretches.

The proof is always in the pudding. If you do something with a specific goal in mind, what you are doing should be able to tangibly move you closer to achieving that goal, and if it doesn’t you’re barking up the wrong tree. Give this a try, and let me know if it works for you.

The AuthorDean Somerset, CSCS, a personal trainer and post-rehab specialist in Edmonton, Alberta, is owner of Somerset Fitness Ltd. He has a degree in kinesiology from the University of Alberta and is certified by the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology and the National Strength and Conditioning Association. He’s written articles for the PTDC as well as T Nation and Bodybuilding.com, and contributed to Men’s Health, Women’s Health, Shape, Men’s Fitness, and many other magazines and websites. You can contact him at his website or Facebook, and check out his unique approach to training on his YouTube channel. |